i’m excited to introduce this month’s guest editor who hails from Wolverhampton, England, Catherine Phoenix Hallam. she wrote a fascinating piece on Predatory Drift — the instant switch in dogs’ play behaviors to seeking behaviors (which can often lead to undesirable outcomes). she’s done an excellent job in presenting the information for the ‘everyday dog owner’ while adding the science for those who are trainers. so depending on your time zone, either grab your morning coffee or a glass of wine and enjoy the read!

~ suzanne

by Catherine Phoenix Hallam, MSc

Last spring I was bumbling along the South Staffordshire Railway when I stopped for a chat with couple of people. We got on to the subject of large dogs playing with smaller dogs as one of mine, the Mighty Mitzy, was playing ‘catch-the-treat’ with much larger breeds — two Stafford Bull Terriers and a Labrador Retriever.

Serendipitously, a woman who was with a different group of folks — who happened to be visiting from the US — struck up conversation about large breeds playing with small breeds as her two dogs had an incident while boarding. She owns a German Shepherd Dog (large dog) and a Terrier-mix (small dog). The boarding facility noted that the PLAY between her dogs became NOT PLAY and this was written to assist her in explaining what had transpired and to give caution going forward. Both of these conversations inspired me to write this piece for dog owners everywhere.

What is Predatory Drift?

Although the term ‘Predatory Drift’ implies the gradual movement from the PLAY circuitry in the brain to the SEEKING circuitry it is not 1. It is an instant switch that happens with observable physiological signals that are antecedents to predatory behaviors.

Dog breeds are wired differently in their brains, through selective breeding processes and selection. Although you can train a breed of dog to do a job that they are not ‘predisposed’ to do, such as teaching a Border Collie to retrieve, there is a genetic predisposition and a 'body conformity' for that specific skill 2 . So, a Border Collie can be trained to do a water retrieve, however they do not have the body conformity — as in body composition — and feel the cold more than a Labrador Retriever.

Let’s now look at PLAY behaviors and SEEKING behaviors.

PLAY Behaviors

According to neuroscientists Panksepp and Biven, the brain circuitry of PLAY is evident with dogs that are relaxed and happy. PLAY does not happen if there is hunger, thirst, pain, discomfort, or threat. If the dog is feeling grief, rage, frustration, anxiety, fear, you will not see PLAY. It is also impeded by an excess of dopamine.

PLAY Behaviors can be seen by the following:

Play signals that are used throughout the PLAY session such as happy play face, play bow.

Larger exaggerated movements (you see this with the puppies that jump and lunge).

Very loose face and body physiology.

Fragmented incomplete behaviors.

Use of other objects such as the chasing of play objects.

Quick responses to the situation that seem very reflexive.

PLAY facilitates some dopamine, and oxytocin, but also has other opioids and neurotransmitters such as Glutamate and Acetylcholine. Play is extremely useful for dogs to learn about emotions of other dogs (or their humans) and to build up some cognitive skills. It supports the dogs in how to build up relationships, how to maintain relationships and how to work cooperatively.

With family dogs in a large group, or extremely familial dogs there may be boisterous play that has a lot of rough and tumble. This is not usually seen in dogs that are unfamiliar or dogs that meet up for an occasional play date. If it is seen a dog may not have 'social skills' or understand the language of the 'dog'.

For puppies and young dogs PLAY helps them through the process of building their non-social skills. These can often be seen in their predatory motor patterns but are truncated (broken bits) or in different orders. When a larger dog then plays with a smaller dog (but not always) there may be a situation through over-arousal whereby the larger dog switches into SEEKING.

SEEKING Behaviors

SEEKING behavior is dopamine-driven and supports the Predatory Motor Pattern (PMP) of that dog. There is an ‘alert arousal’ without any given emotion within this type of SEEKING behavior.

It is not the ‘reward’ or ‘reinforcement’ that is important; it is the ‘SEEKING’ part of the behavior pattern. SEEKING can be involved with other systems — specifically those within the emotional systems. A dog that is SEEKING is highly motivated, highly enthusiastic, as it supports the dog’s exploration and has a high amount of curiosity (think of the Labrador searching for that bit of sausage you threw in the bushes).

The Predatory Motor Pattern (PMP) depends on the type of dog or mix of dog that is in front of you. It’s good to remember that this predatory sequence is a series of motor patterns whereby one pattern triggers the next. With this in mind, the entire PMP is as follows:

orient —> eye —> stalk —> chase —> grab-bite —> kill-bite—> dissect —> consume

The Predatory Motor Pattern (PMP) of Border Collies

Through many decades of selective breeding, Border Collies have the following behaviors that are hypertrophied (these are in capital letters below the photo). In other words, these behaviors are exaggerated. It’s what makes this breed a superior sheepdog/cow-dog.

orient —> EYE —> STALK —> CHASE —> grab-bite —> kill-bite—> dissect —> consume

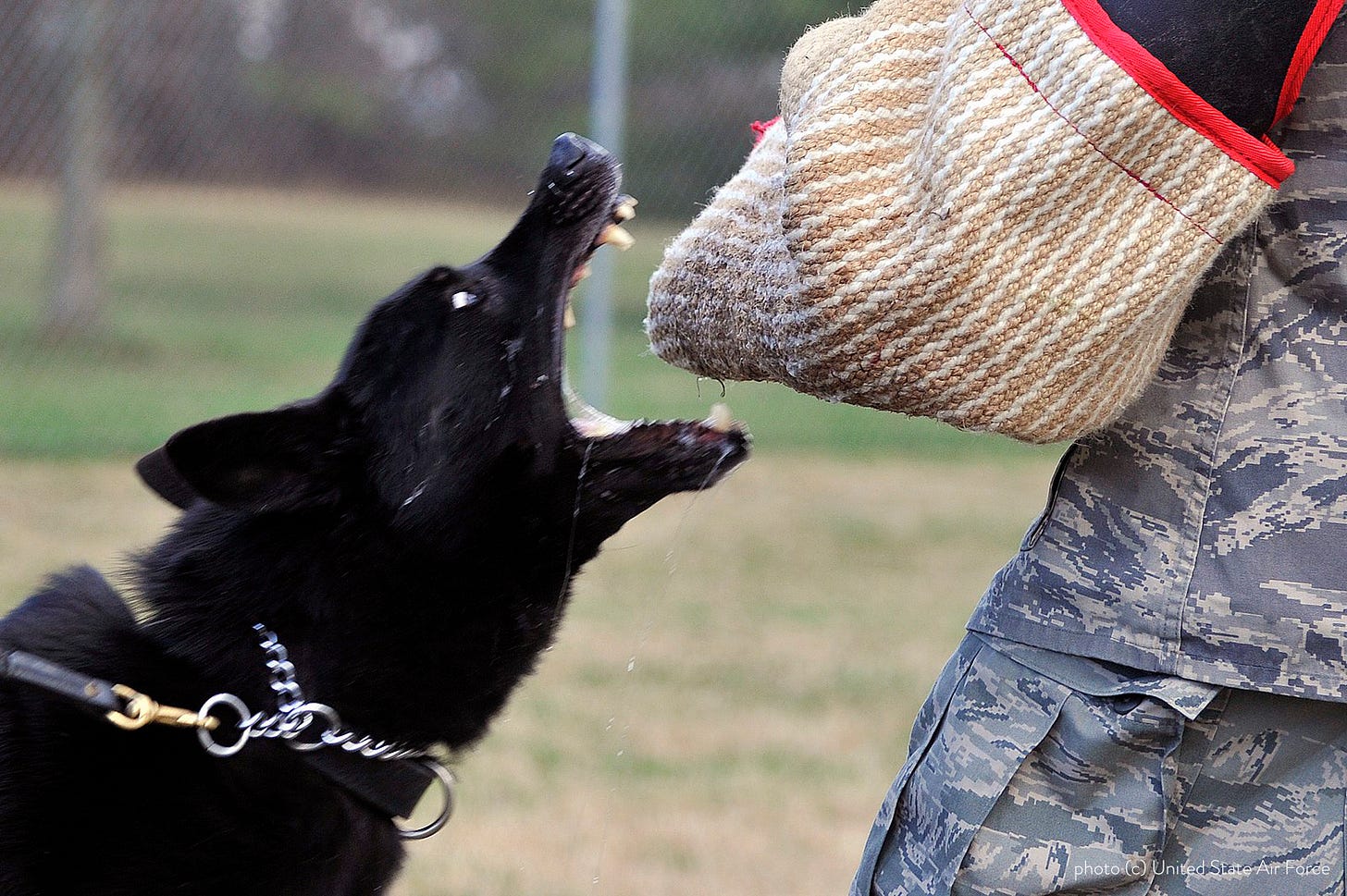

The Predatory Motor Pattern (PMP) of German Shepherds

Let’s now look at the German Shepherd Dog, whose original purpose in the mid-1800s was to herd and protect sheep (and perhaps the shepherd too) and is nowadays largely known as a versatile working dog which happens to also include protection work (family, military, police, security). Its Predatory Motor Pattern may have the CHASE —> GRAB-BITE exaggerated through selective breeding. Its PMP would then look like this: [2][3]

orient —> eye —> stalk —> CHASE —> GRAB-BITE —> kill-bite—> dissect —> consume

How does this affect you?

In a given situation where dogs are at PLAY, there may be a moment when one of the dogs switches from PLAY to SEEKING, called PREDATORY DRIFT.

This is especially prevalent when larger dogs play with smaller ones, increased arousal, with an associative increase in dopamine that supports each pattern part of the PMP; there is the SWITCH and BOOM! It may happen when the little dog makes a squeal, it may be through frustration because the larger dog cannot catch the little dog, or just generally an increased arousal during PLAY. PLAY circuitry is switched off and SEEKING is switched on.

There are often the signals of a change in body language from the above PLAY behaviors to some of the following:

Lip-licking

Intense staring

Fixed mouth

Forward movement of the body

Paw lift

Breathing change

Stiff tail

Ears are forward and stiff

Stillness

Mouth and face are usually stiff although the tongue may be out it is not soft spooned at the end

It may involve a “down & watch” behavior in preparation for the chase. Sometimes it may involve a sit and head curved over behavior.

Some German Shepherds are not inhibited in their mouthing (they tend to be nose-bodgers or open-mouthed on necks, shoulders or even catch the back of legs) this is the ‘GRAB-BITE’ that is in their Predatory Motor Pattern. Also, some breeding lines of German Shepherds may have exaggerated ‘GRAB-BITE’ which facilitates the use of them in security work, bite work, etcetera. On a similar sized dog this is ok as there is a ‘cost benefit analysis’ in injuring a larger dog and the consequences that it may have on the SEEKER.

With a smaller dog this may mean that the larger dog does some damage. This is due to size as well as the sounds that the ‘prey’ (smaller dog) makes when GRAB-BITE is done.

When the switch happens, a dog in SEEKING is not emotional. It is aroused, but not emotional. This is where a dog does not recall (come to you when called) and just focuses on the ‘prey’! The Predatory Motor Pattern is a highly reinforcing innate (internally) suite of behaviors as at every junction of the PMP there is a dopamine fix.

Once a dog does digress and cause injury to a dog through this process, care and I mean CARE needs to be taken in future when exposed to multiple dog interactions. SEEKING is highly reinforcing especially when there has been a completion of the Predatory Motor Pattern. It will be more rewarding than that steak you hold in your hand!

So, what do you do if your dog has performed its PMP and there has been an unfortunate outcome?

Implement these precautions:

Positively introduce the muzzle. A Baskerville Muzzle that is introduced using reward-based learning is beneficial to avoid the dog using their teeth. (Chirag Patel has a great video for this).

Use a harness and a long line for control in a situation where you may come across, game or small dogs.

Practice the recall and proof it.

Avoid instances of leaving family or familial dogs together without supervision. If need be, place your dog in either a pen, crate, kennel, or another room for the dog to relax and rest in when the carers are not present.

Seek the help of a Positive Reward Based Trainer (see Cooper et al, 2014 who found RBT more effective than punishment-based methods in changing chasing behaviors; De Castro et al 2020 – who looked at different schools and the impact on the dog’s physiology and stress behaviors).

So, observe your large dogs around smaller dogs. And yes, as an owner of large dogs it's often the little dogs that are ‘all that' with a massive ‘attitude’. However, it is vital that you, as a dog owner, are aware of this switch and to look out for the change that is evident in their 'body language'.

Hope that wasn't too heavy? An owner that is informed and aware is worth the time that it took to research and write this.

Panksepp, J. and Biven, L. (2012) The Archaeology of Mind: Neuroevolutionary Origins of Human Emotion. USA: W.W. Norton and Co.

Coppinger, R. and Coppinger, L. (2001) Dogs: A Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. New York, USA: Scribner.

Serpell, J. (ed) (2005) The Domestic Dog: Its Evolution, Behavior, and Interaction with People. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cooper, J.J., Cracknell, N., Hardiman, J., Wright, H. and Mills, D. (2014) ‘The Welfare Consequences and Efficacy of Training Pet Dogs with Remote Electronic Training Collars in Comparison to Reward Based Training.’ PloS One 9 e102722 https://doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0102722

Panksepp, J. (2004) Affective Neuroscience: The Foundations of Human and Animal Emotions (Series in Affective Science).’ USA; Oxford University Press

Vieira de Castrol, A.C., Fuchs, D., Morello, G.M., Pastur, S., de Sousa, L. and Olsson, I.A.S. (2020) ‘Does training method matter? Evidence for the negative impact of aversive-based methods on companion dog welfare.’ PloS One 15 e0225023 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225023